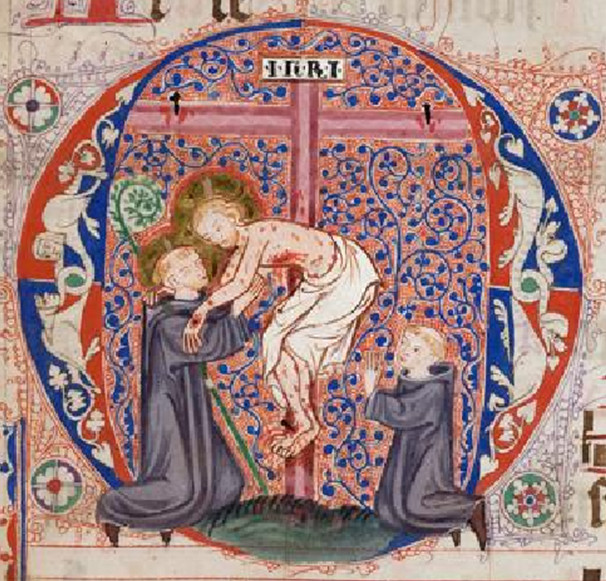

Bernard of Clairvaux

About the text: Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) was one of the earliest members of the Cistercian Order—an attempt at reforming the Benedictines by returning to the Rule of St. Benedict—and certainly its most famous. A skilled preacher and perhaps even a mystic, Bernard’s constant scriptural language and imagery has gained for him the title “last of the Fathers.” His book On Consideration, a portion of which we present here, was written to one of his former monks Pope Eugenius III, to instruct him in what contemporary pop-psychology likes to call “mindfulness.” Bernard invites the Pope to consider the “things that are above” (Col 3:2).

—

Chapter I. That Consideration Is in Exile amongst Material Things.

Although the four preceding books are included with the present under the title “On Consideration,” they are to a great extent concerned with action, because with regard to many particulars they are intended to teach and admonish thee not only of what thou shouldst consider, but likewise of what thou oughtest to do. This fifth book, which I am now beginning, shall treat of consideration alone. For the things that are above thee—which is the part of my subject remaining to be discussed—have no need of thy action, but only invite thy contemplation. There is nothing for thy activity to effect in those objects which abide always in the same state and shall so abide for ever, and some of which have existed from everlasting. Therefore, my most wise and holy Father, I would have thee to understand clearly that as often as thy consideration descends from such high and heavenly things to those that are earthly and visible, whether to study them as sources of knowledge, or to desire them as useful, or to compose and regulate them as thy duty demands: so often does it enter into a land of exile. However, if it occupies itself with material realities in such a way as to make them the means of attaining to the spiritual, its exile will not be very remote. Indeed I may say that by this mode of application to sensible objects it begins to return to its native sphere. For this is the most sublime and worthy use to which earthly creatures can be put, when, as St. Paul of his wisdom tells us, “the invisible things of God are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made” (Rom 1:20). Now, obviously, it is not for the citizens that such a ladder is necessary, but only for exiles. The Apostle was not unaware of this, because after saying that the invisible things of God are seen and understood by means of His visible works, he added significantly, “by the creature of the earth.” And in truth, what need have they of a ladder who have already reached the summit? Such is the case with the creature of heaven, the holy angel, who has ready to hand a means of contemplating those invisible objects more perfectly because more directly. He sees the Word, and in the Word all that the Word has created. Consequently he is under no necessity of seeking a knowledge of the Creator from the works of His hand. And even with regard to these, he has not to descend to them in order to know them, because he contemplates them in the Divine Essence where they are seen far more distinctly and perfectly than in their own natures. Hence the angel does not require the instrumentality of bodily sense for the perception of bodily objects: he is rather a sense to himself and perceives by his spiritual substance. This is the most excellent manner of knowing: when a being is not dependent on any foreign support, but fully self-sufficient to attain to whatever knowledge it pleases. For that which is in want of assistance from outside itself is in the same measure less secure, less perfect, and less free.

But what shall I say of the being which is dependent on the help not only of things outside itself, but even of things subordinate to itself? Is not this kind of dependence preposterous and unworthy? It is surely a dishonour for a noble nature to have to seek assistance from one of inferior degree. Yet from this dishonour no man shall be completely delivered until he has been translated into “the liberty of the glory of the children of God” (Rom 8:21). For then “they shall all be taught of God” (Jn 6:45), they shall all be made happy by God alone without the intervention of any creature. This shall be our repatriation, when, namely, we shall have emerged from the region of bodies and entered the world of spirits, which is nothing else but our God Himself, the Infinite Spirit, and the limitless Home of the happy angels. Let neither the senses nor the imagination expect to find in that Dwelling-Place, viz., in God, anything on which they may be exercised, because all that It contains is Truth, and Wisdom, and Power, and Eternity, and the Sovereign Good. But it is far removed from us so long as we live here below; and meantime the place of our sojourn is a valley of tears where the senses reign supreme and consideration is in exile; where the material organs act with full power and liberty, but where the eye of the soul is clouded and dimmed. What wonder, therefore, that the exile should need the assistance of the native? And happy the wayfarer who, during the time of his pilgrimage, knows how to convert the free favour of the citizens, without which he cannot accomplish his journey, into a bounden service, employing their goods as means, not resting in them as ends; claiming and requisitioning, instead of asking or requesting them.

Chapter II. On the Three Degrees of Consideration.

Great is he who, according to what has been said, regards the service of the senses as the wealth belonging to the natives of this land of his exile, and so endeavours to put it to the best use by employing it for his own and his neighbour’s salvation. Nor less great is he who, by philosophising, uses the senses as a stepping-stone for attaining to things invisible. The only difference is that the latter occupation is manifestly the more pleasant, the former the more profitable: the one demands more fortitude, the other yields greater delight. But greatest of all is he who, dispensing altogether with the use of the senses and of sensible objects, so far at least as is possible to human fragility, is accustomed, not by toilsome and gradual ascents but by sudden flights of the spirit, to soar aloft in contemplation from time to time, even to those sublime and immaterial realities. To this last kind of consideration as I think, belong the transports of St. Paul. For they were rather raptures than ascents: he does not say that he mounted, but that “he was caught up into paradise” (2 Cor 12:4). And in another place he writes, “Whether we be transported in mind, it is to God” (2 Cor 5:13). Now these three degrees are attained in the following manner. Consideration, even in the place of its banishment, by the pursuit of virtue and the help of grace, rises superior to the senses; and then either represses them lest they should wax wanton, or keeps them within due bounds lest they should wander away, or it avoids them altogether lest they should tarnish its purity. In the first it appears more powerful, in the second more free, and more pure in the third. For purity and fervour are the two wings which it uses in its flight.

Dost thou desire me to distinguish each of these three kinds of consideration by its proper name? Well, if it pleases thee, let us call the first “dispensative” consideration, the second “estimative,” and the third, “contemplative.” The meaning of these names will appear from their definitions. Dispensative consideration is that which uses the senses and sensible objects in an orderly and unselfish manner as a means of meriting God; estimative consideration is that which prudently and diligently examines everything and ponders everything in search of God; contemplative consideration is that which, concentrating itself in itself, disengages itself—in so far as it is assisted by divine grace—from all earthly human occupations and interests in order to contemplate God. Notice carefully that contemplative consideration is the fruit of the other two species, and that these latter, unless referred to it, are not really what they are called. For dispensative consideration apart from contemplative, sows much indeed, but reaps nothing; and similarly, out of relation to contemplative, that which I have called estimative advances, I allow, but never reaches its term. Therefore it may be said that what the first prepares, the second enjoys the odour of, and the third the taste. Nevertheless, it is true that both dispensative and estimative consideration can also bring us to the taste, but not so speedily. And as between these, the first attains the goal with more labour, the second with more tranquillity.

—

Taken from Bernard of Clairvaux, Treatise on Consideration, trans. a priest of Mount Melleray (Dublin: Browne and Nolan, Limited, 1921), 145-150. https://archive.org/details/stbernardstreati00bern/page/144/mode/2up?view=theater

Leave a Reply